The spine tunnel developments at Gascoigne Wood were the longest and most complex mining developments ever undertaken in the UK. The south spine Robbins T.B.M. was the first to be completed on 22nd June 1987. The north spine tunnel, driven by a Thyssen Meco ( Paurat ) Titan E134C Roadheader, was completed on 24th November 1990.

The south spine tunnel was equipped with 14,885 horsepower ( 10,100KW ), 1.3m wide, 28.1mm thickness, steel cord conveyor capable of carrying 2200 tonnes of coal per hour at a speed of up to 8,4m/sec . It was 12,232m in length and weighed 2,500 tonnes when empty and transported coal 805m from lowest point to surface. The drive was a Direct drive, twin E frame DC winder motors (5050kw) and was designed by Anderson Strathclyde and REI and was the most powerful conveyor in the world when installed.

Information plate on A.S.L.Conveyor Drive

It was designed to handle the entire coal production of the Selby Coalfield and was the first of the spine tunnels to be fully operational.

Gascoigne Wood South Spine Steel Cord Conveyor.

The North Spine tunnel, when operational was equipped with a 11,084 horsepower (8750 kw), direct drive, twin D frame winder motors rated at 4375 kw, 1.05m wide cable belt. The length of the conveyor was 9,650m with a tandem accelerator conveyor, 3,000m in length and 1.35m wide, loading from the inbye end, on to the cable belt.

The Cable Belt Tandem Conveyor.

Both conveyors were capable of 2,000 tonnes per hour. It was designed by Cable Belt Conveyors Limited and was also capable of handling the full production of all the five mines.

Wistow Staple Bunker delivering coal on to the cable belt.

Deputy inspecting the cable belt

When the Selby Complex was fully operational the Gascoigne Wood spine tunnels were fed from the five producing mines via multiple vertical bunkers. The staple bunkers were supplied with coal from the Barnsley seam which is 60m above the Gascoigne Tunnels.

During production the Gascoigne Wood conveyors had to run constantly and stoppages were very rare due to the sheer amount of production from the five mines. Any stoppages, other than safety related , were planned so that production could be re- directed to either of the main conveyors. At the bottom of each staple bunker, a monitored and controlled feed of coal was achieved using Westerland Feeders. These feeders had load cells so coal feeds could be measured and controlled. All the bunkers were controlled by Gascoigne Wood surface control room. The feed of coal was delivered via hoppers with hydraulic doors, each with a capacity of 85 tonnes and could direct the coal supply to either of the spine tunnel conveyors. During the spine tunnel developments a system of boreholes from Wistow Mine to Gascoigne were planned for access. The borehole at V3s was a small bore staple shaft. The next cross slit at V4s was originally a single bunker but later became West and East staple bunkers, at 4.5m diameter, each with a Westerland weigh feeder. The coal clearance from Wistow Mine to Gascoigne Wood Mine started in January 1983 in order to start production at Wistow Mine in July 1983.

Wistow Mine staple bunkers and boreholes

As the Gascoigne Wood spine tunnels progressed further staple shafts and access shafts were made. At 7208m a ventilation shaft from Wistow was made. The next cross slit was called V7s where a staple shaft was sunk. The next cross slit was V8s where two staple bunkers were sunk with access ladders to Wistow Mine.

V8s Heading during construction.

V8s cross slit when completed.

Vent slit during construction.

This cross slit had a north and south staple bunker when completed. Just inbye of this slit at 7916m, a second ventilation shaft was constructed and the shaft at 7208m was disused.

Wistow Mine staple shafts and boreholes

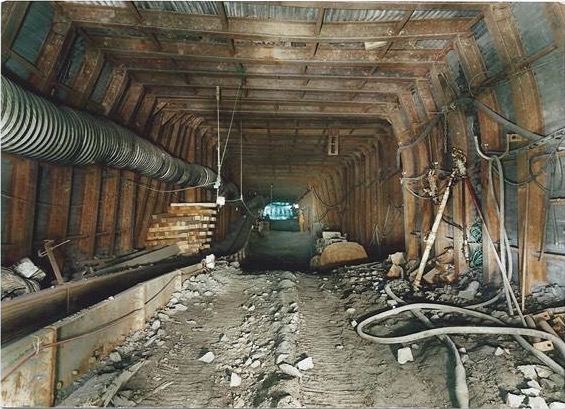

The south spine Robbins TBM tunnel progressed very well , but the north spine tunnel slowed due to very bad ground conditions which required back ripping at a later date.

Amco heading men back ripping in South Spine Tunnel.

In early 1986 The south spine Robbins TBM heading broke the world record for a Tunnel Boring Machine when the AMCO heading teams mined a record of 19m in one shift, 43m in a day and 152.4 metres in a week breaking a record from 1981.

The world record breaking AMCO Heading Teams January 1986

The next production connection was with Stillingfleet Mine. This staple bunker was a revised version of original plans to have dedicated staple bunkers at Stillingfleet Mine and North Selby Mines. The revised plan was to have a conveyor through Stillingfleet Mine from North Selby Mine and deliver the combined production through one staple shaft when North Selby was in full production.

Stillingfleet / North Selby Connection.

The south spine tunnel progressed well until late 1986 when the TBM hit very soft conditions. The tunnel boring machine was unable to cut in the soft rock and virtually stopped. A connection with Riccall Mine was imperative as the coal production from Riccall and Whitemoor Mines depended on Gascoigne Wood for the coal clearance. The only answer was a heading from Riccall Mine back towards Gascoigne Wood so a heading started from Riccall Mine in early 1987. The Stillingfleet Connection heading was well established, when the south spine TBM overcame the soft conditions using a concrete grouting system. The heading progressed well to the final point and completed the spine tunnel on the 22nd June 1987.

Gascoigne Wood Spine Tunnel connection with Riccall Mine at completion of both Spine Tunnels.

As you can see from the plan above the ventilation borehole, access borehole and coal clearance staple shafts are shown.

A 1in 7 drift connection was made from Riccall and booster fans were installed and powered from a dedicated supply in Riccall Mine pit bottom substation.

To ensure the safe access and egress in and between the spine tunnels at Gascoigne Wood Mine, cross slits were made as mentioned in a previous post. These were used for ventilation, substations, loco pass byes, charging stations, for the locomotive fleet, pumping stations, staple bunker access and ventilation/ access boreholes. To enable the safety of the men in the case of a fire in the spine tunnels, smoke doors were installed in these slits. The doors could be operated remotely from the surface control room in an emergency situation.

One of the V slits with electrical equipment and conveyor control panels.

V11s ventilation slit smoke doors

To keep the 25km of spine tunnels stone dusted, was as you can imagine, a major job. Planning was imperative to attain high standards in such a massive complex of tunnels and cross slits due to distances to travel. Gascoigne Wood used various methods of applying the stone dust.

Cryogenic stone dust train

The cryogenic (compressed nitrogen) system was used to deliver huge amounts of stone dust in the spine tunnels. This system was used at most of the mines in around the Selby Coalfield.

Cryogenic stone duster in use.

Cryogenic stone duster in use.

Stone dusting at a Westerland feeder slit in the south spine tunnel.

Compressed air was available along the spine tunnels with compressor house situated at various points. It was used for stone dusting at transfer points as seen above using the hopper and lance.

Keeping the conveyors maintained and safe was also a huge job. A system was devised to replace defective rollers using a loco mounted portable lifting station to take the weight off the conveyor of the defective roller to enable replacement. Inspection were done using a purpose designed loco carriage which was low slung to enable inspections on the move.

Replacing a defective conveyor roller on the ASL conveyor.

Conveyor inspection train.

Teams of men were also deployed to keep the spillage to a minimum. As you can imagine moving 12 million tonnes of coal along a conveyor system will always cause some level of spillage.

ASL conveyor spillage.

Cable belt spillage.

Compressor Houses.

As mentioned earlier compressed air was used throughout the spine tunnels. Back ripping was another job which required regular attention. Long sections of both spine tunnels were backripped and dinted. Cable bolting was also used at various points in the tunnels.

Installing 26 ft cable bolts.

Gascoigne Wood had a fleet of Clayton BoBo locomotives for transporting men and equipment from the drift bottom to inbye working areas. Due to the sheer length of the tunnels, loco charging and battery changing stations were sited along the tunnels in either specially widened roadway or passbye slits.

Changing a BoBo battery.

Becorit equipment for changing batteries.

My sincere thanks to Neil Rowley for allowing me to use his photographs and information.