When the NCB started it’s drilling program in 1964 they began with a series of 5 boreholes at Kelfield, Whitemoor, Barlow, Cambleforth and Hemingbrough. When the core samples were analysed they found the Barnsley seam running from the West at Kelfield at over 2.44m thick to the East at Whitemoor at over 2.13m thick.

The Selby Coalfield core sample.

The N.C.B geologist said that in the Selby area the most important find is the Barnsley seam. The seam is widely worked in the Barnsley and Doncaster area and is 3 metres thick but splits into 2 seams called the Warren House and the inferior Low Barnsley seam towards Askern Colliery and beyond. In the Selby area the seam combines to a seam very similar to the one worked in Barnsley. The next phase was to prove the extent and quality of the seam so a drilling program was started in 1972. At the end of 1972 a core sample taken in Cawood showed the seam was over 3 metres thick. Further samples in the 110 square miles of the coalfield proved the seam was up to 3.4 metres thick. The true extent was discovered and 600 million tonnes of Barnsley coal was available in the Selby area. The next problem was how to mine it. The person in charge of the project was Mr Bill Forrest, deputy director of the North Yorkshire are of the N.C.B.

Selby is an attractive, unspoilt area of Yorkshire and very rural. Many farming villages reside in the area with little heavy industry. The two rivers, the Ouse and Wharf flow through the area, which is a very low lying area and prone to flooding. Subsidence was raised as a major worry which could cause cause further flooding problems. Many villages had very old pretty churches and the main one was Selby Abbey, a beautiful, Norman arched church.

Selby Abbey.

The industries found in the proposed coalfield were condensed around the town of Selby and consisted of RHM flour mill, BOCM Silcock animal feeds, a chemical plant, John and E. Sturge producing citric acid, a pickle and bacon factory and Cochrane’s shipbuilders, but the biggest business in the area was a very important business on a massive scale, the farming land.

The NCB quickly realised that opening a mine on this scale in such an area was going to be problematic and that coal mining could become the largest industry and employer in the area quite understandably raised fears among the local communities. For many people a major worry was the influx of hundreds if not thousands of miners and their families. Some local senior officials , who were against the mine even planned to show films and slides to show what mining communities were like, asking the question, “is this for you?” portraying miners as somehow different from the local community. This was a huge issue to be overcome.

Another major worry, especially in the farming communities was subsidence. Selby, as mentioned earlier has 2 rivers running through the area. The area, very much like the Doncaster coalfield has a huge system of drainage dikes due to the high water table in the area which can cause major flooding. Many local people remembered the floods of 1947 where the River Ouse over topped its banking system and flooded large areas, and even flooded the town of Selby. The local farming community had read many stories in farming magazines, about prize agricultural land being reduced to bog and marsh land especially by private mining companies who provided no payments for damage after mining . They quite rightly needed to know what was going to happen when the subsidence inevitably happened and what the payments for lost land were going to be. Farming and living near to the rivers was a particular worry. Subsidence damage to large industrial buildings was also raised and particularly the churches and Selby Abbey.

Many other fears were raised such as the size of the mine headgears, heavy construction traffic, and noise and dirt associated with such a massive project on the local villages. The NCB had a massive task to win over the local people and knew that developing a ten million tonne coal mine project could not be achieved without people being aware it was happening.

The NCB had an ace up their sleeve in the fact that energy prices had become very volatile. The event causing this major issue with energy prices in the country and the whole of the Western world was the Yom Kippur War. It was a similar situation to the Ukraine War when oil supply was cut back and prices rose very quickly. The west was hit with a huge hike in prices for oil imports, so the government looked at the vast reserves of coal in the UK. to replace the cheap imports of oil, used for generation of energy, as a replacement. The North Sea was proving a vast reserve of oil and gas but coal was seen as the fuel of the future of the power generation needs of the country. The Selby Coalfield was worth £250m (£3.3 bn in 2025) a year towards balancing the government books so became a priority.

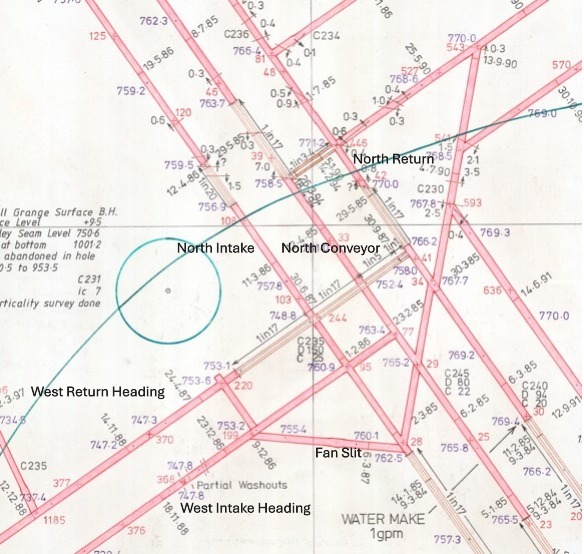

In 1974 the plan for the Selby Coalfield was made with application for planning permission made clear. One drift mine and five satellite pits, to mine 29,00 hectares of the Barnsley Seam to be delivered to Drax power station via a dedicated rail link. The development of the mine sites was to be a separate issue to be discussed.

In 1973, decisions had been made about the NCBs approach to the local communities about the Selby project. Peter Walker, the Industry secretary and Derek Ezra, who was NCB Chairman, said Selby would be a clean mine and would not have the usual industrial mess associated with mining. Derek Ezra said Selby would be totally different to previous mining areas with different headgears, less pollution, no dirty coal preparation plants, traffic and railway sidings. These were very difficult aims to achieve, but they did show the NCB had set a very high bar for the project to be environmental friendly. These objectives proved to be more difficult than expected.

The NCB set about telling the communities about the environmentally friendly mine from day one. They felt that the people in the area should be made aware of what they were doing to ensure cooperation and information was forthcoming. Local groups were invited to meetings and fact finding sessions. People in the Selby area were provided with copies of the NCB Selby Newsletter, explaining how the Selby project was to work setting out its position and how the new miners and families would be “integrated not segregated” into communities.

The effect in some quarters was that the NCB was raising false hope, that the project was too good to be true and getting local approval for an environmentally friendly pit and then announcing a less palatable truth when the project started.

One of the major issues raised was the height of the headgears. The NCB in the early stages of the project said the winder towers would be unlike any other mines ever developed. They said that the use of winch gear instead of winders would allow the level of the towers to be as low as 40 feet or 12 metres, which would easily be hidden from view. The NCB revisited the calculations and realised that standard engineering of mine winders changed the height of the winder towers to 96 feet to allow for the 16 tonne loads required to be lifted and lowered in the shafts. These towers were still substantially lower than existing collieries and were still barely visible.

Some local people accused the NCB of not telling the entire truth about the project but some saw the mistakes as a part of trying to tell the local people what was happening as the planning process was progressing, including changes made along the way and changes made as the project evolved.

The NCB. looked at various options to mine the vast Selby reserves but once the environmental realisation was accepted the only way to mine the coal was the one drift mine and five satellite pits. This had been tried and tested, all be it on a smaller scale at the Longannet Mine in Scotland.

In 1973 and 1974 the Selby Mine project was very high on the list of the local community’s thoughts. Many different opinions about the project were expressed from comments of “Fighting tooth and nail against the rape of our countryside” to “a coalmine will be a gold mine”. The only way to have a fully rounded review of the Selby project was a public enquiry. The NCB had put in a planning application for the huge project which inevitably meant everyone had to have a say on the outcome of the project. Another option of a Planning Inquiry Commission could have been called by the government, but this was rejected in favour of a Selby Coalfield Public Enquiry.

Bibliography

Ezra, Derek (1976). Coal Technology for Britain’s Future. London: Macmillan.